As a photographer I find reflections to be a fun and

artistic tool, offering many creative possibilities. For this reason, I am

always excited when the opportunity arises for me to include them in my

compositions. From the viewers perspective, reflections add interest to images

by challenging their visual perception.

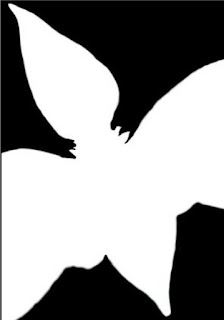

Being a nature photographer, the reflective surface

appearing most often in my images is water. When water is perfectly still it

takes on a magical mirror like quality that is very beautiful. In situations

like this I often like to create images that celebrate the symmetry between the

main subject and its reflection, as in this image of a Blacksmith Plover from

Africa.

Being a nature photographer, the reflective surface

appearing most often in my images is water. When water is perfectly still it

takes on a magical mirror like quality that is very beautiful. In situations

like this I often like to create images that celebrate the symmetry between the

main subject and its reflection, as in this image of a Blacksmith Plover from

Africa.

When creating images like this I make every effort to keep

the image clean and simple, working hard to eliminate anything in the

composition that will detract from the symmetry.

This next image is from a canyon in Utah. It celebrates

another type of reflection I like to play with, which I call a “light

reflection”. For this composition, I have included a shaded section of stream.

Reflected in the water of this stream is a red rock wall that is fully lit by

the rising sun, creating a beautiful stream of molten gold. Surprisingly I

often use a polarizer when creating images like this. Which seems

counter-intuitive because polarizers are often used to remove reflections but

in this instance I will use the polarizer to intensify the colors. I look

through my camera as I rotate the polarizer until I get the effect I like.

This next image is from a canyon in Utah. It celebrates

another type of reflection I like to play with, which I call a “light

reflection”. For this composition, I have included a shaded section of stream.

Reflected in the water of this stream is a red rock wall that is fully lit by

the rising sun, creating a beautiful stream of molten gold. Surprisingly I

often use a polarizer when creating images like this. Which seems

counter-intuitive because polarizers are often used to remove reflections but

in this instance I will use the polarizer to intensify the colors. I look

through my camera as I rotate the polarizer until I get the effect I like. For this image of a Wood Duck pair created in Ohio I have

combined both principals. In addition to the duck’s reflection we also have a

reflection of sunlit foliage reflected in the water around them which adds a

serious “punch” of color to the background. To maximize this effect, it is

important that the sunlit reflection be reflected in a shaded part of the

water.

For this image of a Wood Duck pair created in Ohio I have

combined both principals. In addition to the duck’s reflection we also have a

reflection of sunlit foliage reflected in the water around them which adds a

serious “punch” of color to the background. To maximize this effect, it is

important that the sunlit reflection be reflected in a shaded part of the

water.

When creating images of reflections changing your

perspective either higher or lower will often have a big impact on the quality

and position of the reflection in your final image. So find the elevation which

creates the best reflection and composition then make your image. Also on a

technical note, when I am making images like this I tend to stop the lens down

a bit more ensuring I can keep both the main subject and the reflection itself

sharp.

Good Luck and Good Light!

Steve

Over the course of his 30-year

career, Steve Gettle has spent countless hours creating hundreds of thousands

of photographs capturing nature’s beauty around us. Steve’s images communicate

his love for the wildlife and the wild places of our world. He has had his images shown in many exhibitions and publication. Steve especially enjoys sharing his

knowledge through both private and group location-based experiences focused on

individual nature photography development in once-in-a-lifetime locations.

Over the course of his 30-year

career, Steve Gettle has spent countless hours creating hundreds of thousands

of photographs capturing nature’s beauty around us. Steve’s images communicate

his love for the wildlife and the wild places of our world. He has had his images shown in many exhibitions and publication. Steve especially enjoys sharing his

knowledge through both private and group location-based experiences focused on

individual nature photography development in once-in-a-lifetime locations.

Over the course of his 30-year

career, Steve Gettle has spent countless hours creating hundreds of thousands

of photographs capturing nature’s beauty around us. Steve’s images communicate

his love for the wildlife and the wild places of our world. He has had his images shown in many exhibitions and publication. Steve especially enjoys sharing his

knowledge through both private and group location-based experiences focused on

individual nature photography development in once-in-a-lifetime locations.

Over the course of his 30-year

career, Steve Gettle has spent countless hours creating hundreds of thousands

of photographs capturing nature’s beauty around us. Steve’s images communicate

his love for the wildlife and the wild places of our world. He has had his images shown in many exhibitions and publication. Steve especially enjoys sharing his

knowledge through both private and group location-based experiences focused on

individual nature photography development in once-in-a-lifetime locations.

Wilderness Images

The Nature Photography of Steve Gettle

8877 River Valley Ct.

Brighton, MI 48116

Office 810-231-8118

Fax 810-231-8119

Website http://www.stevegettle.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/steve.gettle

Steve will be teaching "Frozen Moments: High Speed Nature Photography" on Saturday, November 19th.

Steve's program is sponsored by Cognisys - Capture the Hidden World

To see the entire schedule of CAPS-Chicago Area Photography School classes go to: caps.caccaweb.com or click here: Home

Steve will be teaching "Frozen Moments: High Speed Nature Photography" on Saturday, November 19th.

Steve's program is sponsored by Cognisys - Capture the Hidden World

To see the entire schedule of CAPS-Chicago Area Photography School classes go to: caps.caccaweb.com or click here: Home

To register go to: Chicago Area Photographic School (CAPS) 2017 | Summary | powered by RegOnline